Scroll and hover to read.

Contested Canvas

Coppoolse, A., Chan, K.M. and Yu, W.C. (2020),

Nuart Journal 4 Freedom (visual essay): pp. 87-95.

In the summer of 2019, the streets of Hong Kong became a global stage of a still ongoing fight against authoritarianism. This was not the first time for the territory to find its otherwise carefully maintained and seemingly orderly public realm turn into a space for political mobilisation in response to increasingly diminishing freedoms. Yun Chung Chen and Mirana M. Szeto (2017: 69-72) argue that this kind of resistance began with Occupy Queen’s Pier in 2007 when an attempt was made to stop the demolition of the Pier, which was a significant transport hub but also an important civic space. Since this Occupy movement of 2007, there have been several moments in which important spaces in Hong Kong were reclaimed through collective civil disobedience and with the intention to ‘speak in the face of power’ (Chen & Szeto 2017: 80). Indeed, as Chen and Szeto (2017: 81) assert, the reclamation of public space in Hong Kong ‘has been a means for political mobilization and building of civic and political subjectivity in a context of growing political repression’. paragraph. Click here to add your own text and edit me. It's easy.

‘Hongkongers, rise up!’ and ‘Disband police’ written on a Jersey barrier, while hotel Eaton HK’s billboard features in the background. Graffiti can be found everywhere, especially around main roads where marches take place. Messages of protest have become part of daily life. Attempts are made to cover them up, but in a context where the authorities choose suppression over listening, freshly painted surfaces invite new messages to appear. Jordan, Kowloon, Hong Kong, 2019. Photograph ©Yu Wing Ching.

What is new to the movement of 2019 is the explosion of written notices of discontent in the spaces of the city. Don Mitchell (2003: 35) contended that it is not predetermined ‘publicness’ that makes a space public, but that it is a particular group in society that makes space public through either deliberate or unplanned actions. Hong Kong’s public spaces have become ‘contested terrains’ (Loukaitou-Sideris & Ehrenfeucht 2009: 30) through physical occupation, but citizens have also resisted the ‘disciplinary demands’ (Geyh 2009: 1) of the urban spaces in which they live through a visual occupation of the walls of these terrains. Rather, the public’s demands to have its voices heard have been made through a reclamation of what could be called a ‘contested urban canvas’. Hong Kong’s façades, windows, bus stops, underpasses, and any other of its wall-like surfaces have been occupied and repurposed as canvasses for ‘voicing out’ – something common in many parts of the world, but relatively uncommon in the context of Hong Kong until quite recently.

‘Communist bank’, ‘Say no to RMB4’, ‘Liberate Hong Kong’, ‘Revolution of our time’, ‘Our leader is conscience’. Mainland Chinese banks use white construction hoarding to cover their damaged shop fronts, providing ample space for graffiti. Prince Edward, Kowloon, Hong Kong, 2019. Photograph ©Yu Wing Ching.

The walls of Hong Kong’s contested terrains were initially covered in coloured memos, followed by increasingly well-organised poster arrangements. Soon, however, more ‘permanent’ messaging emerged around the urban areas of the territory – Hong Kong’s sporadic graffiti writing quickly developed into rich spatio-textual discourses not only around the so-called Lennon Walls, but along the entire stretch of urban space where marches and gatherings were held. More specific locations in the city also invited painterly correspondences. Particularly, façades of government buildings, entrances of MTR2 stations, and shop fronts of businesses that are outspokenly pro-Beijing turned into critical canvasses of sorts. Hanauer (2011: 316) suggested that ‘the uncensored nature of graffiti writing (or to be more exact, the illegal nature of all graffiti writing) creates a situation in which competing political understandings can be presented’. In Hong Kong, this competition of opposing political ideas plays out not just between one graffiti text

and another,but it eventuates in a visual power play that involves the erasing of these texts and their subsequent reappearance.

The act of ‘covering up’. The windows of MTR entrances have been covered up with iron plates, plaster, and fresh paint. Jordan, Kowloon, Hong Kong, 2019. Photograph ©Anneke Coppoolse.

Billboards at tram stops have been taken down and replaced with white boards; an open invitation to graffiti, which gets erased by the authorities not long after it appears. A competition of opposing political understandings results in painterly abstraction. Central, Hong Kong Island, Hong Kong, 2019. Photograph ©Chan Ka Man.

While the urban canvas is reclaimed in pursuit of freedom, constant attempts are made at a visual silencing of the voices on Hong Kong’s walls through different tactics. Urban façades are written on, yet are often quickly painted over, brushed out, or otherwise covered up. In this competition of voices and their erasure, the public space becomes an active space for discourse. With every attempt at concealing messages of revolt, the authorities and other institutions of power both produce obvious markers that uncover their intended ‘silencing’, and unintentionally encourage more graffiti precisely by creating new and quite perfect empty canvasses. Indeed, where coloured memos and posters were relatively easily (though never entirely) erased – leaving behind scraps of paper; remainders of discontent; visual proof of societal scarring – the attempts at erasing

Hong Kong’s graffiti that ‘speaks in the face of power’ have led to a kind of political dialoguing between voices and silences. This is the contested canvas of Hong Kong: in a political context where the authorities have chosen not to listen but to suppress, urban walls become canvasses that not only present ‘competing for political understandings but also record failing attempts at concealing discontent.

Perfect canvasses are created unintentionally, ‘covering up’ damaged walls and inviting fresh graffiti writing at the next protest or sooner. Central, Hong Kong Island, Hong Kong, 2019. Photograph ©Chan Ka Man.

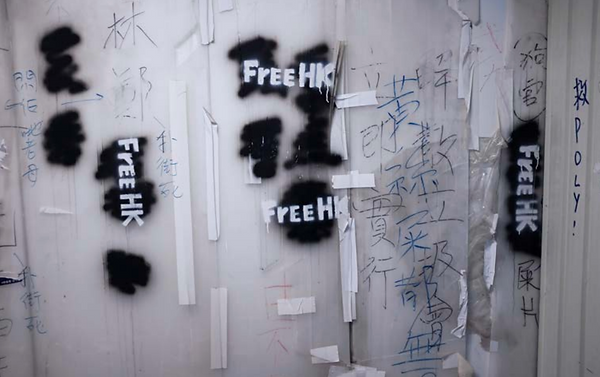

Initial messages of discontent on a white surface had been covered with black paint. These are markers of intended ‘silencing’. Yet, opposing responses soon emerged. Jordan, Kowloon, Hong Kong, 2019. Photograph ©Anneke Coppoolse.